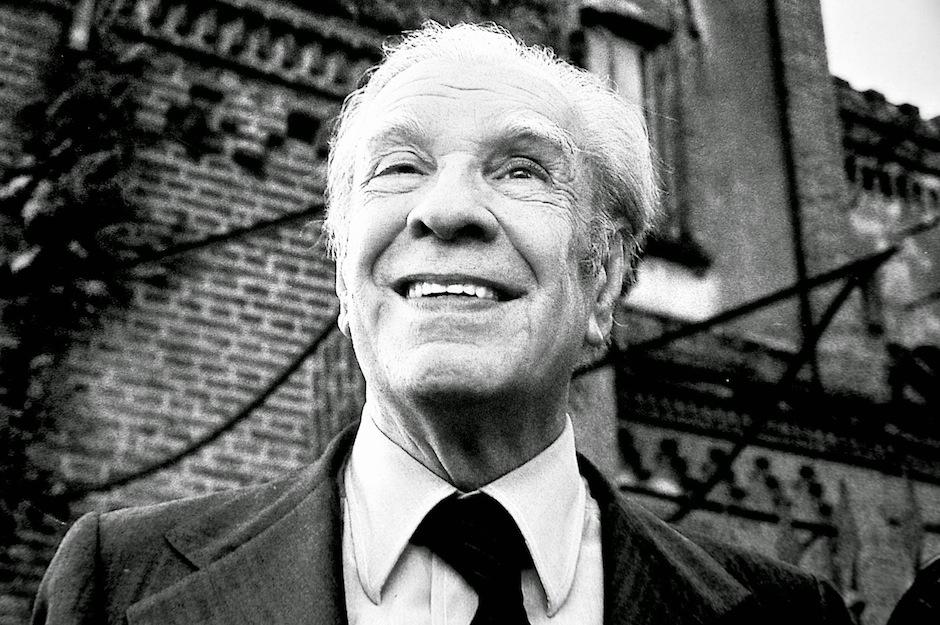

This legendary Argentine poet, essayist, and short-story writer's works have become classics of 20th-century world literature, leaving a legacy that serves as an enduring testament to the politics and passions of Jorge Luis Borges. Jorge Luis Borges, August 24, Born August 24th, 1899 in Buenos Aires, Argentina, Jorge Franciso Isidoro Luis Borges Acevedo was a coveted writer, famed for his short stories, essays, poetry and for his work as a translator, During his writing career, he produced many 20th century classics such as Ficciones (1944) and El Aleph (1949) which contributed to rendering him a lead icon in Latin. Jorge Luis Borges is a monumental inscription in the world of philosophical fiction. His short stories with his labyrinthine themes and language have been explored and analyzed to the point that he has been named one of the pioneers of post-modernist fiction.

Returning home from the Tarbuch and Loewenthal textile mills on the 14th of January, 1922, Emma Zunz discovered in the rear of the entrance hall a letter, posted in Brazil, which informed her that her father had died. The stamp and the envelope deceived her at first; then the unfamiliar handwriting made her uneasy. Nine or ten lines tried to fill up the page; Emma read that Mr. Maier had taken by mistake a large dose of veronal and had died on the third of the month in the hospital of Bage. A boarding-house friend of her father had signed the letter, some Fein or Fain from Rio Grande, with no way of knowing that he was addressing the deceased’s daughter.

Emma dropped the paper. Her first impression was of a weak feeling in her stomach and in her knees; then of blind guilt, of unreality, of coldness, of fear; then she wished that it were already the next day. Immediately afterward she realized that that wish was futile because the death of her father was the only thing that had happened in the world, and it would go on happening endlessly. She picked up the piece of paper and went to her room. Furtively, she hid it in a drawer, as if somehow she already knew the ulterior facts. She had already begun to suspect them, perhaps; she had already become the person she would be.

In the growing darkness, Emma wept until the end of that day for the suicide of Manuel Maier, who in the old happy days was Emmanuel Zunz. She remembered summer vacations at a little farm near Gualeguay, she remembered (tried to remember) her mother, she remembered the little house at Lanus which had been auctioned off, she remembered the yellow lozenges of a window, she remembered the warrant for arrest, the ignominy, she remembered the poison-pen letters with the newspaper’s account of 'the cashier’s embezzlement,' she remembered (but this she never forgot) that her father, on the last night, had sworn to her that the thief was Loewenthal. Loewenthal, Aaron Loewenthal, formerly the manager of the factory and now one of the owners. Since 1916 Emma had guarded the secret. She had revealed it to no one, not even to her best friend, Elsa Urstein. Perhaps she was shunning profane incredulity; perhaps she believed that the secret was a link between herself and the absent parent. Loewenthal did not know that she knew; Emma Zunz derived from this slight fact a feeling of power.

She did not sleep that night and when the first light of dawn defined the rectangle of the window, her plan was already perfected. She tried to make the day, which seemed interminable to her, like any other. At the factory there were rumors of a strike. Emma declared herself, as usual, against all violence. At six o’clock, with work over, she went with Elsa to a women’s club that had a gymnasium and a swimming pool. They signed their names; she had to repeat and spell out her first and her last name, she had to respond to the vulgar jokes that accompanied the medical examination. With Elsa and with the youngest of the Kronfuss girls she discussed what movie they would go to Sunday afternoon. Then they talked about boyfriends and no one expected Emma to speak. In April she would be nineteen years old, but men inspired in her, still, an almost pathological fear. . . Having returned home, she prepared a tapioca soup and a few vegetables, ate early, went to bed and forced herself to sleep. In this way, laborious and trivial, Friday the fifteenth, the day before, elapsed.

Impatience awoke her on Saturday. Impatience it was, not uneasiness, and the special relief of it being that day at last. No longer did she have to plan and imagine; within a few hours the simplicity of the facts would suffice. She read in La Prensa that the Nordstjarnan, out of Malmo, would sail that evening from Pier 3. She phoned Loewenthal, insinuated that she wanted to confide in him, without the other girls knowing, something pertaining to the strike; and she promised to stop by at his office at nightfall. Her voice trembled; the tremor was suitable to an informer. Nothing else of note happened that morning. Emma worked until twelve o’clock and then settled with Elsa and Perla Kronfuss the details of their Sunday stroll. She lay down after lunch and reviewed, with her eyes closed, the plan she had devised. She thought that the final step would be less horrible than the first and that it would doubtlessly afford her the taste of victory and justice. Suddenly, alarmed, she got up and ran to the dresser drawer. She opened it; beneath the picture of Milton Sills, where she had left it the night before, was Fain’s letter. No one could have seen it; she began to read it and tore it up.

To relate with some reality the events of that afternoon would be difficult and perhaps unrighteous. One attribute of a hellish experience is unreality, an attribute that seems to allay its terrors and which aggravates them perhaps. How could one make credible an action which was scarcely believed in by the person who executed it, how to recover that brief chaos which today the memory of Emma Zunz repudiates and confuses? Emma lived in Almagro, on Liniers Street: we are certain that in the afternoon she went down to the waterfront. Perhaps on the infamous Paseo de Julio she saw herself multiplied in mirrors, revealed by lights and denuded by hungry eyes, but it is more reasonable to suppose that at first she wandered, unnoticed, through the indifferent portico. . . She entered two or three bars, noted the routine or technique of the other women. Finally she came across men from the Nordstjarnan. One of them, very young, she feared might inspire some tenderness in her and she chose instead another, perhaps shorter than she and coarse, in order that the purity of the horror might not be mitigated. The man led her to a door, then to a murky entrance hall and afterwards to a narrow stairway and then a vestibule (in which there was a window with lozenges identical to those in the house at Lanus) and then to a passageway and then to a door which was closed behind her. The arduous events are outside of time, either because the immediate past is as if disconnected from the future, or because the parts which form these events do not seem to be consecutive.

During that time outside of time, in that perplexing disorder of disconnected and atrocious sensations, did Emma Zunz think once about the dead man who motivated the sacrifice? It is my belief that she did think once, and in that moment she endangered her desperate undertaking. She thought (she was unable not to think) that her father had done to her mother the hideous thing that was being done to her now. She thought of it with weak amazement and took refuge, quickly, in vertigo. The man, a Swede or Finn, did not speak Spanish. He was a tool for Emma, as she was for him, but she served him for pleasure whereas he served her for justice.

When she was alone, Emma did not open her eyes immediately. On the little night table was the money that the man had left: Emma sat up and tore it to pieces as before she had torn the letter. Tearing money is an impiety, like throwing away bread; Emma repented the moment after she did it. An act of pride and on that day. . . Her fear was lost in the grief of her body, in her disgust. The grief and the nausea were chaining her, but Emma got up slowly and proceeded to dress herself. In the room there were no longer any bright colors; the last light of dusk was weakening. Emma was able to leave without anyone seeing her; at the corner she got on a Lacroze streetcar heading west. She selected, in keeping with her plan, the seat farthest toward the front, so that her face would not be seen. Perhaps it comforted her to verify in the insipid movement along the streets that what had happened had not contaminated things. She rode through the diminishing opaque suburbs, seeing them and forgetting them at the same instant, and got off on one of the side streets of Warnes. Paradoxically her fatigue was turning out to be a strength, since it obligated her to concentrate on the details of the adventure and concealed from her the background and the objective.

Jorge Luis Borges

Aaron Loewenthal was to all persons a serious man, to his intimate friends a miser. He lived above the factory, alone. Situated in the barren outskirts of the town, he feared thieves; in the patio of the factory there was a large dog and in the drawer of his desk, everyone knew, a revolver. He had mourned with gravity, the year before, the unexpected death of his wife — a Gauss who had brought him a fine dowry — but money was his real passion. With intimate embarrassment, he knew himself to be less apt at earning it than at saving it. He was very religious; he believed he had a secret pact with God which exempted him from doing good in exchange for prayers and piety. Bald, fat, wearing the band of mourning, with smoked glasses and blond beard, he was standing next to the window awaiting the confidential report of worker Zunz.

He saw her push the iron gate (which he had left open for her) and cross the gloomy patio. He saw her make a little detour when the chained dog barked. Emma’s lips were moving rapidly, like those of someone praying in a low voice; weary, they were repeating the sentence which Mr. Loewenthal would hear before dying.

Things did not happen as Emma Zunz had anticipated. Ever since the morning before she had imagined herself wielding the firm revolver, forcing the wretched creature to confess his wretched guilt and exposing the daring stratagem which would permit the Justice of God to triumph over human justice. (Not out of fear but because of being an instrument of Justice she did not want to be punished.) Then, one single shot in the center of his chest would seal Loewenthal’s fate. But things did not happen that way.

In Aaron Loewenthal’s presence, more than the urgency of avenging her father, Emma felt the need of inflicting punishment for the outrage she had suffered. She was unable not to kill him after that thorough dishonor. Nor did she have time for theatrics. Seated, timid, she made excuses to Loewenthal, she invoked (as a privilege of the informer) the obligation of loyalty, uttered a few names, inferred others and broke off as if fear had conquered her. She managed to have Loewenthal leave to get a glass of water for her. When the former, unconvinced by such a fuss but indulgent, returned from the dining room, Emma had already taken the heavy revolver out of the drawer. She squeezed the trigger twice. The large body collapsed as if the reports and the smoke had shattered it, the glass of water smashed, the face looked at her with amazement and anger, the mouth of the face swore at her in Spanish and Yiddish. The evil words did not slacken; Emma had to fire again. In the patio the chained dog broke out barking, and a gush of rude blood flowed from the obscene lips and soiled the beard and the clothing. Emma began the accusation she had prepared ('I have avenged my father and they will not be able to punish me. . .'), but she did not finish it, because Mr. Loewenthal had already died. She never knew if he managed to understand.

The straining barks reminded her that she could not, yet, rest. She disarranged the divan, unbuttoned the dead man’s jacket, took off the bespattered glasses and left them on the filing cabinet. Then she picked up the telephone and repeated what she would repeat so many times again, with these and with other words: Something incredible has happened. . . Mr. Loewenthal had me come over on the pretext of the strike. . . He abused me, 1 killed him . . .

Actually, the story was incredible, but it impressed everyone because substantially it was true. True was Emma Zunz’ tone, true was her shame, true was her hate. True also was the outrage she had suffered: only the circumstances were false, the time, and one or two proper names.

Translated by D. A. Y.

ThreeVersions of Judas*

Jorge Luis Borges

There seemed a certainty in degradation.

- T. E. Lawrence, Seven Pillars of Wisdom

In Asia Minor or in Alexandria, in the second century of our faith(when Basilides was announcing that the cosmos was a rash and malevolentimprovisation engineered by defective angels), Nils Runeberg might havedirected, with a singular intellectual passion, one of the Gnostic monasteries.Dante would have destined him, perhaps, for a fiery sepulcher; his name mighthave augmented the catalogues of heresiarchs, between Satornibus andCarpocrates; some fragment of his preaching, embellished with invective, mighthave been preserved in the apocryphal Liber adversus omnes haereses ormight have perished when the firing of a monastic library consumed the lastexample of the Syntagma. Instead, God assigned him to the twentiethcentury, and to the university city of Lund. There, in 1904, he published thefirst edition of Kristus och Judas; there, in 1909, his masterpiece Demhemlige Frälsaren appeared. (Of this last mentioned work there exists aGerman version, Der heimliche Heiland, published in 1912 by EmilSchering.)

Before undertaking an examination of the foregoing works, it isnecessary to repeat that Nils Runeberg, a member of the National EvangelicalUnion, was deeply religious. In some salon in Paris, or even in Buenos Aires, a literary person might well rediscover Runeberg's theses; but thesearguments, presented in such a setting, would seem like frivolous and idleexercises in irrelevance or blasphemy. To Runeberg they were the key with whichto decipher a central mystery of theology; they were a matter of meditation andanalysis, of historic and philologic controversy, of loftiness, of jubilation,and of terror. They justified, and destroyed, his life. Whoever peruses thisessay should know that it states only Runeberg's conclusions, not his dialecticor his proof. Someone may observe that no doubt the conclusion preceded the'proofs'. For who gives himself up to looking for proofs of somethinghe does not believe in or the predication of which he does not care about?

The first edition of Kristus och Judas bears the followingcategorical epigraph, whose meaning, some years later, Nils Runeberg himselfwould monstrously dilate:

Not one thing, but everything tradition attributes to Judas Iscariotis false.

(De Quincey, 1857.)

Preceded in his speculation by some German thinker, De Quincey opinedthat Judas had betrayed Jesus Christ in order to force him to declare hisdivinity and thus set off a vast rebellion against the yoke of Rome; Runebergoffers a metaphysical vindication. Skillfully, he begins by pointing out howsuperfluous was the act of Judas. He observes (as did Robertson) that in orderto identify a master who daily preached in the synagogue and who performedmiracles before gatherings of thousands, the treachery of an apostle is notnecessary. This, nevertheless, occurred. To suppose an error in Scripture isintolerable; no less intolerable is it to admit that there was a singlehaphazard act in the most precious drama in the history of the world. Ergo, thetreachery of Judas was not accidental; it was a predestined deed which has itsmysterious place in the economy of the Redemption. Runeberg continues: TheWord, when It was made flesh, passed from ubiquity into space, from eternityinto history, from blessedness without limit to mutation and death; in order tocorrespond to such a sacrifice it was necessary that a man, as representativeof all men, make a suitable sacrifice. Judas Iscariot was that man. Judas,alone among the apostles, intuited the secret divinity and the terrible purposeof Jesus. The Word had lowered Himself to be mortal; Judas, the disciple of theWord, could lower himself to the role of informer (the worst transgressiondishonor abides), and welcome the fire which can not be extinguished. The lowerorder is a mirror of the superior order, the forms of the earth correspond tothe forms of the heavens; the stains on the skin are a map of the incorruptibleconstellations; Judas in some way reflects Jesus. Thus the thirty pieces ofsilver and the kiss; thus deliberate self-destruction, in order to deservedamnation all the more. In this manner did Nils Runeberg elucidate the enigmaof Judas.

The theologians of all the confessions refuted him. Lars PeterEngström accused him of ignoring, or of confining to the past, the hypostaticunion of the Divine Trinity; Axel Borelius charged him with renewing the heresyof the Docetists, who denied the humanity of Jesus; the sharp tongued bishop ofLund denounced him for contradicting the third verse of chapter twenty-two ofthe Gospel of St.

Luke.

These various anathemas influenced Runeberg, who partially rewrotethe disapproved book and modified his doctrine. He abandoned the terrain oftheology to his adversaries and postulated oblique arguments of a moral order.He admitted that Jesus, 'who could count on the considerable resourceswhich Omnipotence offers,' did not need to make use of a man to redeem allmen. Later, he refuted those who affirm that we know nothing of theinexplicable traitor; we know, he said, that he was one of the apostles, one ofthose chosen to announce the Kingdom of Heaven, to cure the sick, to cleansethe leprous, to resurrect the dead, and to cast out demons (Matthew 10:7-8;Luke 9:1). A man whom the Redeemer has thus distinguished deserves from us thebest interpretations of his deeds. To impute his crime to cupidity (as somehave done, citing John 12:6) is to resign oneself to the most torpid motiveforce. Nils Runeberg proposes an opposite moving force: an extravagant and evenlimitless asceticism. The ascetic, for the greater glory of God, degrades andmortifies the flesh; Judas did the same with the spirit. He renounced honor,good, peace, the Kingdom of Heaven, as others, less heroically, renouncedpleasure.1 With a terrible lucidity he premeditated his offense.

In adultery, there is usually tenderness and self-sacrifice; inmurder, courage; in profanation and blasphemy, a certain satanic splendor.Judas elected those offenses unvisited by any virtues: abuse of confidence(John 12 :6) and informing. He labored with gigantic humility; he thoughthimself unworthy to be good. Paul has written: Whoever glorifieth himself,let him glorify himself in the Lord. (I Corinthians 1:31); Judas soughtHell because the felicity of the Lord sufficed him. He thought that happiness,like good, is a divine attribute and not to be usurped by men.2

Jorge Luis Borges Born

Many have discovered post factum that in the justifiable beginningsof Runeberg lies his extravagant end and that Dem hemlige Frälsaren is a mereperversion or exacerbation of Kristus och Judas. Toward the end of 1907,Runeberg finished and revised the manuscript text; almost two years passedwithout his handing it to the printer. In October of 1909, the book appearedwith a prologue (tepid to the point of being enigmatic) by the Danish HebraistErik Erfjord and bearing this perfidious epigraph: In the world he was, andthe world was made by him, and the world knew him not (John 1:10). Thegeneral argument is not complex, even if the conclusion is monstrous. God,argues Nils Runeberg, lowered himself to be a man for the redemption of thehuman race; it is reasonable to assume that thesacrifice offered by him was perfect, not invalidated or attenuatedby any omission. To limit all that happened to the agony of one afternoon onthe cross is blasphemous.3 To affirm that he was a man and that he wasincapable of sin contains a contradiction; the attributes of impeccabilitasand of humanitas are not compatible. Kemnitz admits that the Redeemercould feel fatigue, cold, confusion, hunger and thirst; it is reasonable toadmit that he could also sin and be damned. The famous text 'He willsprout like a root in a dry soil; there is not good mien to him, nor beauty;despised of men and the least of them; a man of sorrow, and experienced inheartbreaks' (Isaiah 53:2-3) is for many people a forecast of theCrucified in the hour of his death; for some (as for instance, Hans LassenMartensen), it is a refutation of the beauty which the vulgar consensusattributes to Christ; for Runeberg, it is a precise prophecy, not of onemoment, but of all the atrocious future, in time and eternity, of the Word madeflesh. God became a man completely, a man to the point of infamy, a man to thepoint of being reprehensible - all the way to the abyss. In order to save us,He could have chosen any of the destinies which together weave the uncertainweb of history; He could have been Alexander, or Pythagoras, or Rurik, orJesus; He chose an infamous destiny: He was Judas.

In vain did the bookstores of Stockholm and Lund offer thisrevelation. The incredulous considered it, a priori, an insipid and laborioustheological game; the theologians disdained it. Runeberg intuited from thisuniversal indifference an almost miraculous confirmation. God had commandedthis indifference; God did not wish His terrible secret propagated in theworld. Runeberg understood that the hour had not yet come. He sensed ancientand divine curses converging upon him, he remembered Elijah and Moses, whocovered their faces on the mountain top so as not to see God; he rememberedIsaiah, who prostrated himself when his eyes saw That One whose glory fills theearth; Saul who was blinded on the road to Damascus; the rabbi Simon ben Azai,who saw Paradise and died; the famous soothsayer John of Viterbo, who went madwhen he was able to see the Trinity; the Midrashim, abominating the impious whopronounce the Shem Hamephorash, the secret name of God. Wasn't he, perchance,guilty of this dark crime? Might not this be the blasphemy against the Spirit,the sin which will not be pardoned (Matthew 12:3)? Valerius Soranus died forhaving revealed the occult name of Rome; what infinite punishment would be hisfor having discovered and divulged the terrible name of God?

Intoxicated with insomnia and with vertiginous dialectic, NilsRuneberg wandered through the streets of Malmö, praying aloud that he be giventhe grace to share Hell with the Redeemer.

He died of the rupture of an aneurysm, the first day of March 1912.The writers on heresy, the heresiologists, will no doubt remember him; he addedto the concept of the Son, which seemed exhausted, the complexities of calamityand evil.

up1 Borelius mockingly interrogates: Why did he not renounce torenounce? Why not renounce renouncing?

up2 Euclydes da Cunha, in a book ignored by Runeberg, notesthat for the heresiarch of Canudos, Antonio Conselheiro, virtue was 'akind of impiety almost.' An Argentine reader could recall analogouspassages in the work of Almafuerte. Runeberg published, in the symbolist sheetSju insegel, an assiduously descriptive poem, 'The Secret Water': thefirst stanzas narrate the events of one tumultuous day; the last, the findingof a glacial pool; the poet suggests that the eternalness of this silent waterchecks our useless violence, and in some way allows and absolves it. The poemconcludes in this way:

The water of the forest is still and felicitous,

And we, we can be vicious and full of pain.

up3 Maurice Abramowicz observes: 'Jesus, d'apres cescandinave, a toujours le beau role; ses deboires, grace a la science destypographes, jouissent d'une reputation polyglotte; sa residence detrente-trois ans parmis les humains ne fut, en somne, qu'unevillegiature.' Erfjord, in the third appendix to the

Jorge Luis Borges El Sur

Christelige Dogmatik, refutes this passage. He writes that thecrucifying of God has not ceased, for anything which has happened once in timeis repeated ceaselessly through all eternity. Judas, now, continues to receivethe pieces of silver; he continues to hurl the pieces of silver in the temple;he continues to knot the hangman's noose on the field of blood. (Erfjord, tojustify this affirmation, invokes the last chapter of the first volume of theVindication of Eternity, by Jaromir Hladlk.)

Translator unknown.* From: 'Artificios' (1944). In the introduction, Borges writes: 'Schopenhauer, De Quincey, Mauthner, Shaw, Chesterton, León Bloy, form the heterogenic census of the authors I continually re-read. In the christological fantasy titled 'Three Versions of Judas' I think I perceive the remote influence of the last [Bloy].'